Do you ever feel like you’re running with one leg only?

Or balancing better on one foot?

Is one hamstring always tighter than the other?

All of the above are common physical problems, and while these little side-to-side asymmetries might catch your attention once in a while, they often remain benign curiosities.

Other times, however, these imbalances can take on a life of their own, impacting the way you move or perform certain physical activities, leading you down a path toward compensations, stiffness, and pain.

Which is why today I want to try something different: a case study of a client who came in last week with right plantar fasciitis—pain and inflammation on the undersurface of the foot—that is limiting her ability to walk and run.

To be crystal clear, this isn’t just a post about resolving foot pain. But we will use the client-in-question’s issue as our jumping-off point into the much broader topic of asymmetry, as well as how these discrepancies can have far-flung implications on your health and performance.

Buckle your seat belt, there’s a lot I want to teach you.

But first, a video.

So….

Why is this otherwise fit, athletic, healthy young lady’s leg shaking like a leaf in a rainstorm while performing such a simple exercise?

I’m glad you “asked.” Allow me to explain.

First, the little tremors you’re seeing on the video are called fasciculations, or involuntary muscle tremors. These reflexive contractions occur when your brain can’t coordinate the action between muscles.

Here, I’ve put her in a position where she has to contract her hamstring by pulling down on the wall, and calf, while lifting her heel off the wall at the same time. This co-contraction—fancy word for what I just described—is essential for normal stride mechanics during walking and running.

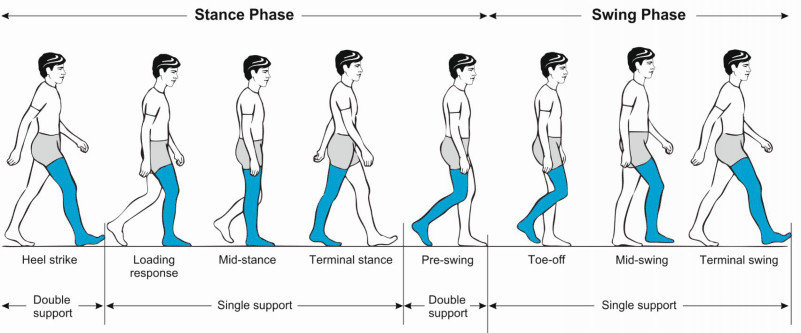

As you can see on the video, she’s struggling mightily. In particular, when she lowers her heel toward the wall—and her calf has to lengthen as her hamstring remains active. These simultaneous demands mimic the early and mid-stance phases of the gait cycle from the picture above.

Relating this back to running, she’s able to coordinate the propulsive actions of these muscles—the push from her foot to her right—but is fighting the lengthening/yielding action—which must occur to accept weight on her left foot as it comes back from her right.

And that’s just laying on her back. Imagine what has to happen when you layer gravity, ground reaction forces, and cardiorespiratory fatigue into the mix. Something has to give.

In her case, it was the tissue on the arch of her foot, on the other side.

Remember, she has right plantar fasciitis. Even though she’s having trouble coordinating her left leg, in the video.

This is what I meant when I said this article isn’t just a case study in foot pain, it’s about how imbalances in one part of the system often show-up as problems in other, seemingly unrelated parts.

Now, here’s what I haven’t told you:

Before I chose this particular exercise—and a few others—we went through three assessments, which painted a picture of movement that mapped neatly onto her complaint—right foot pain.

This is what we did:

ASSESSMENT

Modified Ober’s Test

The Modified Ober’s Test is a proxy measure of pelvic position. To oversimplify, a “neutral” alignment of the pelvis allows your ball and socket to fit together all nice and cozy, providing a clear foundation for the movement of your hip joint.

Should there be a change in that alignment, your hip will lose certain ranges of motion. (The exact motions that might be limited depend on the specific orientation).

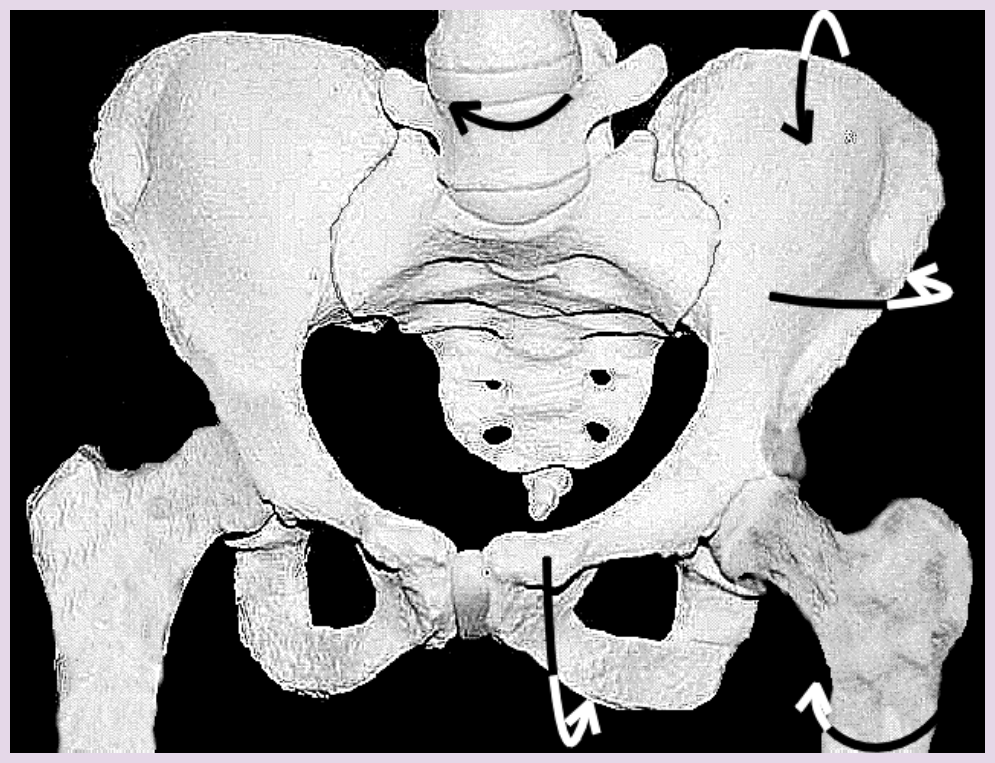

Based on the physics of your hip, we know that a loss of extension (ability to bring your leg behind you) and adduction (ability to cross your knee past midline) is indicative of a forwardly rotated pelvis.

She passed the test on her left side but not on her right. As a practical matter, that means she’ll have trouble shifting “into” her left hip, limiting her ability to get her foot underneath her center of mass on that side when walking and running.

Muscularly, her left hamstring is in a lengthened position—because it’s attached to the backside of her forwardly-tipped left pelvis—making her left calf biased toward plantar flexion—foot pointing away from your body.

The sum total of these changes in hip position is that she has better leverage to push-off her left foot/leg, but will struggle to accept weight back onto it.

That’s why you see her leg shaking when her heel is coming toward the wall (a lengthening/braking contraction) not when it’s moving away (a shortening/propulsive contraction). Her left foot lacks a strong connection to the ground.

It’s not a strength or mobility thing. What she’s “missing” is the ability to coordinate her calf lengthening while holding tension in her hamstring, exactly what needs to happen during a mid-stance position in gait.

Her left foot isn’t fully “connected” to the ground. As a result, she’s defaulting into a neuro-reflexive motor behavior—the shakes—via accessory muscles (quadriceps) in an attempt to regain stability.

(Note: To peek deeper down this rabbit hole, whenever our brains encounter environments that are unfamiliar or potentially threatening—in this case, a lack of stability and connection to the ground—you see a change in activity away from the more modern, evolved regions of our brain toward older, more primitive areas that govern threat response and reflexive behaviors.

It’s the same reason you might forget the substance of a presentation when you’re in front of a large audience. Or become irritable and prone toward impulse purchases when you’re hungry (i.e., “hangry”). Stress changes everything. But, I digress).

Back to my homegirl’s hips…

Active Straight Leg Raise (ASLR)

I previously wrote about the ASLR as it relates to breathing mechanics, but basically this is a confirming test I use to increase the reliability of the Ober’s Test. As I mentioned, if your pelvis—one side or both—tips forward, then your hamstring, which is attached to the backside of the pelvis, will become over-lengthened, limiting normal range of motion.

As suspected, her ASLR was limited on the left versus the right. Indicating a pelvis more anteriorly rotated on that side.

Hip Internal/External Rotation

Lastly, I checked hip internal and external rotation. Due to the internal mechanics of skeletal joints, movement always occurs in three dimensions—around a vertical, horizontal, and transverse axis.

When you have movement or position change along one axis, it necessarily creates changes in the other two. In this case, a forwardly rotated pelvis on the left leads to a change in the orientation of the pelvis to the right.

When this happens—the pelvis rotating towards the right—you would expect to see a change in range of motion values at the hips joints along a transverse, or rotational axis, limiting hip external rotation on the right, because, like the over lengthened hamstring on the left, the glute on the right is also in a stretched position, decreasing its ability contract and “push off” of the right foot.

That’s why you see decreased hip external rotation on the right versus left, secondary to the pelvis internally orienting over the right leg.

Here’s where the right plantar fasciitis comes in.

When you can’t push yourself with your right hip (i.e., your glute max) to center over your left leg as you’re running around the neighborhood, then your right calf and the plantar surface of your foot have to pull double duty to keep you running forward.

Nobody likes to work two jobs. Injuries, if nothing more, are simply tissues that have been asked to do more than they can handle.

Now What?

To summarize, our tests show a bias in skeletal position toward loading on the right leg—accepting weight—and propelling on the left leg—unloading weight.

Her left hamstring and adductor are in a lengthened position, along with her right glute. The effect is that it’s challenging for her to both push-off her right leg and then accept weight back onto her left during walking and running.

So, I gave her three exercises that specifically address these limitations.

Wall Stride

This was the exercise featured in the “shaky leg” video at the beginning. Here, we’re working on co-contraction of the left hamstring (isometrically) and calf (concentrica and eccentric) to improve coordination of her running stride.

Right Glute Max

Using gravity and a resistance band, here we’re “turning on” the right glute in order to push and rotate the pelvis back toward the left. Keeping it real: notice my right foot wants to turn out when I’m doing this exercise and I wiggle around a bit to re-position it forward. That’s my body’s way of “gaming” the drill, moving my knee higher by turning out my foot and ankle instead of using my hip musculature.

Adductor Side Plank

Finally, the adductor plank activates the left inner thigh to pull the pelvis toward the same side, closing the gap between the femur and pelvis, and restoring adduction and extension measures on that side.

Wrap Up

So, that was a peek into my thought process as it relates to movement. To be transparent, I’ve left out more than I’ve shared about the assessment and exercise selection.

These are just the starting points. Eventually, we’ll progress these exercises from laying on the ground to upright, dynamic activities that look and feel a lot more like running and training. Because that’s her goal, to be fit and active and enjoy life. Not just becoming better at exercise.

Maybe foot pain isn’t your thing. Perhaps it’s a stiff back or neck, an achy shoulder, or “trick” knee you want to figure out. It’s hard to know where to start.

If any of these rings familiar and you’re sick of guessing what your next move should be, then getting a personalized plan and coaching might be right for you.